Reflecting on Brexit with ‘Passport to Pimlico’

Let’s go back to the Britain of 1949. A country disfigured and discombobulated by years of war and a population increasingly frustrated with the politics of austerity. It shouldn’t be too hard to imagine.

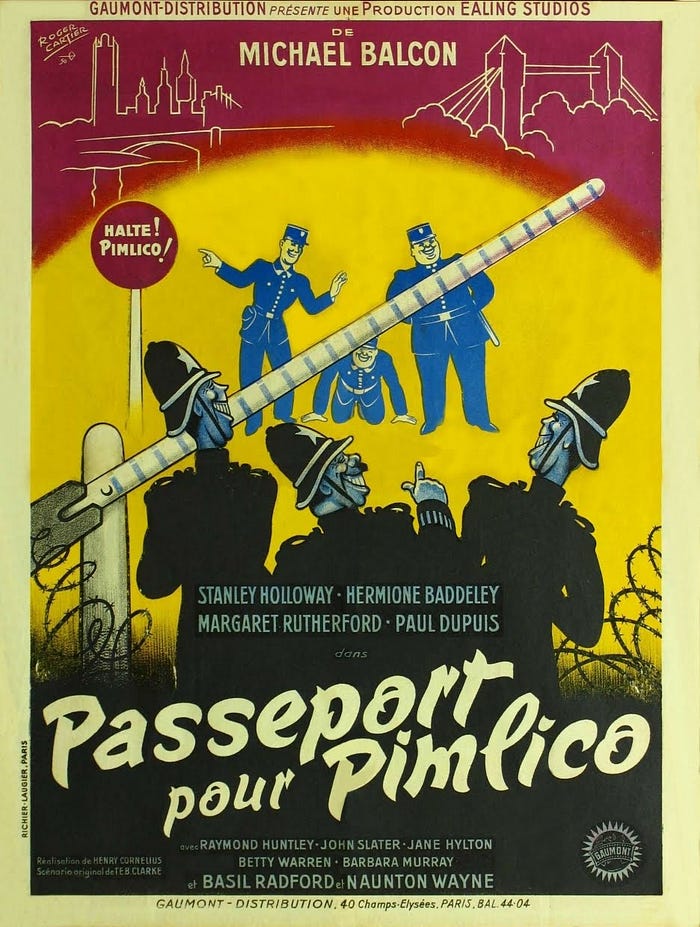

In all of the humdrum and gloom, British cinema frequently offered comic relief and one classic example of this, responding very directly to the living conditions of the day, was Ealing Studios’ Passport to Pimlico. For me, it seems relevant now that Britain has voted to leave the European Union. Why? Well, the film is a topsy turvy take on borders, sovereignty, Britishness — and Europeanness.

(NOTE: There are spoilers below! You may want to watch the film — I highly recommend it — and then come back.)

Passport to Pimlico is set in the London district of the same name, now more famous for spies and eye-watering house prices. Though back in the late forties it was still home to many ordinary Londoners — it was as quintessential as you could get.

And in this Ealing Studios comedy, those Londoners are flung a surprising windfall. An unexploded bomb is accidentally exploded, revealing a long-lost cellar housing many treasures once owned by the Duke of Burgundy. The loot is a great boon — but that’s not all. They also unearth a centuries-old decree left by the Duke annexing Pimlico, of all places, to the medieval Kingdom of Burgundy. As a constitutional historian soon points out, the act has never been repealed so technically Pimlico remains a part of the Kingdom — in fact, the only surviving part.

Overnight, the residents realise they aren’t British at all, they’re Burgundians. And they now have their own micronation to play with. The implications of this are, first and foremost, sharply anti-austerity. Gone is rationing, restrictive rules on street selling, laws on when pubs should close and so on. It quickly turns in to a bloody great — and, ironically, very British — party.

Significantly, the shackles of the establishment are gleefully thrown off, too. Whitehall is rudely snubbed, and a border around Pimlico subsequently erected. Even the local bank manager has his triumph. “Legally, this is Burgundy,” he tells his stuffy boss. “Head Office no longer has any jurisdiction over this bank. This is my bank.”

The Burgundians have swiftly “taken back control” of their lives. And for a while, they’re in heaven. The film’s real attraction for original audiences must chiefly have been this delicious fantasy — a momentary wonderland in which the misery of post-war austerity is cheekily escaped.

Commenting on the film last week, the Irish Times quipped, “Essentially Pimlico Brexits into Europe.” That’s one way of putting it. The film does indeed explore the question of what it means to be free. Interestingly, however, Britishness is the antithesis of this choice. Freedom comes via a forgotten relic of continental Europe — a piece of history that the residents of Pimlico realise they can revive. The European Union, incidentally, would only be founded decades later.

But these are details. The point is that, following secession, blessed autonomy arrives. Film producers of the 1940s could hardly have got away with such an idea if there wasn’t a balance-restoring moral to tell by the end, though. And, indeed, the Burgundians’ frivolity does not last.

Before long, awkward realities become clear. Little Burgundy is cut off from essential utilities and frozen out of trade. Their indulgence begins to get the better of them. There is some hesitation, but eventually a diplomatic and constitutionally acceptable basis for rejoining Great Britain is found. Everyone then has a big street party which, aptly, is ruined by rain just before the credits roll.

The idea of taking control was central to the Burgundians’ fervour for their new-found identity, but it was also their undoing. Soon enough, they discovered that they had not gained control at all, but instead handed their fate over to the forces that surrounded them. Powerless to survive on their own, they had no choice but to accept the need to sober up and start afresh.

Britain, the United Kingdom and, yes, Europe as a whole — these have always been, by definition, unions of factions. Our histories are littered — completely littered — with examples of awkward alliances, secessions and annexations.

Perhaps we should take the moral tale of Passport to Pimlico and apply it to our own situation. Perhaps not. Either way, I do think the film reveals a lot about people’s innate desire for both identity and sovereignty. These things are, for better or worse, rooted in our culture — they have certainly been bubbling there for a long time.

Passport to Pimlico is, above all else, an excellent way of reminding ourselves that the forces around us are bigger than we are. Sometimes those forces are excruciating and unfair. But sometimes they are precisely what liberate us from disaster.